Dear Asrar Jamayee,

Some of my friends complain that I keep writing letters to the dead people. But I cannot stop myself from dashing this missive off to you now that you are no more. It is a closure to the pains that had grounded you, put you in oblivion for years. Now that you have been relieved of multiple pains, I try to pen this tribute.

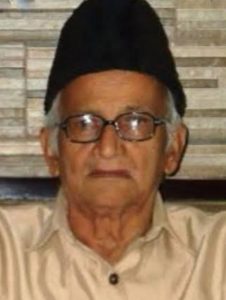

The last time I met Asrar Jamayee (1937-2020) was a couple of years ago at Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s grandnephew and currently Maulana Azad National Urdu University (MANUU) Chancellor Firoz Bakht Ahmed’s house at the crowded Zakir Nagar in Delhi. Though an octogenarian and frail, Asrar nevertheless retained the humour in his talk that had characterized him. Mazahiya shair or humorous poet that is what distinguished him from others. He presented me a copy of Tanzpaey, a collection of his humorous poems. Self-respect tried to stop you from accepting the price that I offered to pay because he said it was a “gift”. But when I insisted and Firoz Bakht persuaded, he accepted it willy-nilly.

Asarar stayed at a one-room rented tenement in Batla House area, his books, papers and many pairs of sherwani laden with dust. He was single and lived alone. Towards the autumn of his life, he remained mostly confined to his room, ignored, disillusioned, uncared for. As if old age-related illnesses and privation were not enough to put hurdles in the path of this once peripatetic poets, a car knocked him down, fracturing one of his arms. His arm in cast, he sat at his room, awaiting help. Help came to him few and far between.

When Firoz Bakht announced on Facebook about the accident that had put the already financially drained and physically weak Asrar sahib in further trouble, I sent my younger brother Dr Mohd Qutbuddin to see him. Dr Qutbuddin drove from JNU to Zakir Nagar, accompanied Firoz Bakht and landed up at Asarar sahab’s tiny, ramshackle room. I had asked my brother to help the poet. He did help him but Firoz Bakht caught the act of giving some money to the old, ill poet on his mobile camera. Firoz Bakht subsequently posted the photograph with a small note on his Facebook wall. It received some snide comments from many who knew Asrar sahib but, I think Firoz Bakht did it only to encourage others to come forward and help the needy poet.

Asrar was cheated multiple times–by others and by his own close relatives. Born Asrar-ul-Haq in a zamindar family in Patna, Asrar’s father Syed Waliul Haq was a student of revolutionary freedom fighter, poet-journalist Maulana Mohammed Ali Jauhar at Jamia Millia Islamia University in Delhi. Jauhar, along with Mahatma Gandhi and a few others, founded Jamia Millia in 1920 and was its first vice-chancellor. Jamia was created as a nationalist institution after a group of students and teachers of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) aligned with the Muslim League and backed its diabolical, divisive policies.

Asrar received a major setback when his own brother fudged documents to grab ancestral properties. He met Dr Zakir Hussain, educationist, former governor of Bihar and later President of India. Zakir Sahab liked his humorous poetry but, a man of vision that he was, he knew writing poetry alone would not ensure him financial stability. So he advised him to finish his Bachelor in Engineering course from BIT, Pilani. But midway this course, Asrar lost his father, returned home only to get entangled in disputes over inherited properties. Earlier, he had earned praise from India’s first President Dr Rajendra Prasad too. Few among today’s generation will believe it, but Dr Rajendra Prasad had initially studied at a madrasa and had learnt Urdu and Persian too.

Dejected, Asrar came to Delhi, adopted the moniker “Jamayee” and became part of the city’s vibrant literary culture. Clad in loose trousers and shirt (in winter he wore sherwani and pyjama), tall, thick glasses framing his face, Asrar would move with a small suitcase in hand. Ministers and politicians, including three former PMS (Rajiv Gandhi, Chandrashekhar, V P Singh, Narasimha Rao) hosted him. Former CM of Bihar Karpoori Thakur was also among his admirers. He was invited over dinner by the powerful politicians whom he regaled with his satirical poems, targeted often to the politicians. His satirical poems on Rajiv Gandhi angered some Congressmen and some of Rajiv’s chamchas even threatened Asrar. When Rajiv Gandhi heard of it, he invited the poet home and enjoyed the humorous, satirical lines he had penned on him.

When the draconian anti-terrorism law, TADA, was brought in in the 1990s, Asrar composed several poems, making fun of how TADA was misused to terrorise people.

I first met him in the mid-1990s at a tiny magazine that I worked for at Nizamuddin West in Delhi. Mr Zeyaul Haq, then executive editor of the magazine, was a connoisseur of Urdu poetry and was fond of Asrar sahab’s sharp satirical lines. Arar Shab would often come there. Seated at Zeyaul Haq Sahab’s cabin, Asarar Sahab would recite his poems, sending us in the peals of laughter. One of the couplets on TADA’s misuse went like this: Hum jo police ke dar se bumpolice mein bhage/Daroga tartaraya TADA mein band kardo (As I bolted myself inside a toilet fear the cops/the daroga asked for arresting me in TADA). Before I heard this, I did not know that public toilets were bumpolice in the local dialect of Delhi and UP.

After the demolition of the Babri Mosque on December 6, 1992, Narasimha Rao began an “outreach to Muslims” programme. A group of Urdu editors were invited to the PM’s house as part of the programme. Asrar who then also edited a newspaper called “Postmortem” was among the invitees. Narasimha Rao too enjoyed his poems that took ample potshots on the shenanigans of the politicians. Explaining the exotic name of the paper, he once said: “Others do postmortem of the dead. I do postmortem of the living.”

The cruelest treatment that this world could have meted out to Asrar was when the Delhi government declared him dead in its registers even when he was alive. A former MLA had helped start a pension of Rs 1500 monthly to Asrar who lived and worked most of his life in Delhi. Somehow, a clerk struck his name off the list of pensioners, denying him the much-needed financial help. He petitioned officers, met local MLA Amanatullah Khan a couple of times, but in vain. Once he confronted the concerned officer, saying: “Aur kya saboot chahiye mere zinda hone ka. Main aapke samne khada hoon (What other proof do you need that I am alive. I am standing before you). Mirza Ghalib had travelled from Delhi to Calcutta to get his suspended pension reopened. Ghalib returned unsuccessful. So did Asrar who never succeeded in convincing the cruel, heartless, insensitive system that he was alive and deserved his pension.

Last winter, a rumour had it that Asrar Jamayee was dead. When he heard it, Asrar stirred his old, creaky bones and came out of his dimly lit, dusty room to declare to the world that he was alive. Now he doesn’t need to do that.

Asrar’s dilemma can be best described in his own words

(translation by Firoz Bakht Ahmed) :

Hamdardi ki lazzat bant rahey hein khushion ke paimaney mein

Kitney dukhi insan hein, yeh koi nahin pehchaney he

Mulkon, mulkon, basti, basti shor hamari jurrat ka

Bachcha, buddha, buddha, tanz hamari janey hei!

They are partying all and celebrating with goblets full of happiness

No one knows the trauma and angst of my life’s sadness

O, the bravery and boldness of my poetry is internationally known

What to talk of adults, even the children are aware of my sadistic groan!

Asrar Jamayee (RIP)

Mohammed Wajihuddin

Journalist, Times of India, Mumbai